There are several reasons for the luxury price tag on

a bottle of Champagne. The biggest one

is the labor-intensive process in which it is made. Unlike still wine, Champagne requires

several added steps involving significant hands-on toil by a cadre of highly-specialized

winery workers. Moreover, the method of

making these hallowed bubbles requires a lengthy period of time. Time is money.

The unique process of making Champagne is one of the

biggest reasons for its lofty price. Once the grape juice ferments to wine,

Champagne goes through an entirely separate process to create its bubbles. This is called the Methode Champenoise and these words appear on every bottle of

sparkling wine made in the Champagne district of France. By law, no other region or country can use

these words, or call their wine Champagne.

The Methode

Champenoise involves a “secondary fermentation” in the bottle. Already fermented still wine is placed in a

bottle along with a tiny amount of sugar and yeasts. A cork is then added. Over the period of several weeks the

added yeast eats the sugar and a secondary fermentation process occurs. Carbon dioxide is a by-product of

fermentation. This carbon dioxide is

responsible for Champagne’s illustrious bubbles.

Dead yeasts from the secondary fermentation must be removed.

Once the yeast cells have consumed all the sugar they

die off. Now, comes the process for

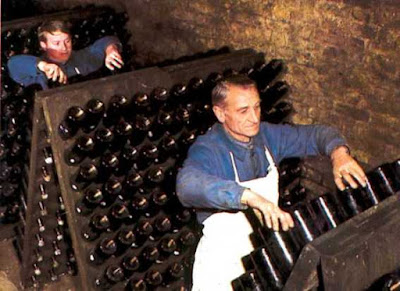

getting rid of the unsightly dead yeast sediment in the bottle. It begins with “riddling.” Bottles are placed in a special rack which

allows them to be very slowly rotated to a vertical position over time (the cork end of

the bottle ultimately ends up at the bottom).

Over a period of several months, each bottle is turned daily by a

“riddler.” Slowly, slowly each bottle is rotated so that

over time the spent yeast cells gravitate toward the neck of the bottle. But,

there’s much more.

Riddlers painstakingly turn each bottle daily

Now that the yeasts have all floated to the neck of

the now positioned vertical bottle, they must be removed. This involves another hands-on process called

“disgorgement.” In short, the bottle is

kept in its vertical position (cork side down) and placed in ice just long

enough for the area near the cork to freeze.

With lightening-speed the cork is removed (and with the cork the frozen dead

yeasts adhering to the cork are also removed), and a new cork is placed….all at

the blink of an eye by a well-seasoned “disgorger.” But

the Champagne is not ready yet. It now

needs to “rest” for months or even years before it is sold.

Dead yeasts accumulate in the vertically positioned bottle & are frozen before removed.

Dead yeasts accumulate in the vertically positioned bottle & are frozen before removed.

Another reason that Champagne is pricey is the notion

of supply and demand. The Champagne region

is the smallest wine region in France and produces a limited number of

bottles. Globally, Champagne accounts

for <1% of total wine production. To

further complicate the issue Champagne is France’s most northern wine

area. There are some years in which

grapes do not ripen adequately, thus further limiting availability and driving

up the cost.

In summary, the Champagne process is long and complex,

with many steps along the way that necessitate workers with well-honed special

skills. Production is limited. All of this translates to do-re-mi for the

consumer. Wine Knows will be visiting both the Champagne and Burgundy regions in June 2019. For more information about this trip visit www.WineKnowsTravel.com.